Photographers Unknown, How Many Times Do I Remember From You

Do I ever remember

certain nights in June of that year,

almost blurry, of my adolescence

(it was in nineteen hundred it seems to me

forty nine)

because in that month

I always felt a restlessness, a small anguish

the same as the heat that began,

nothing else

than the special sound of the air

and a vaguely affective disposition.

They were the incurable nights

and fever.

The high school hours alone

and the untimely book

next to the wide open balcony (the street

freshly watered it disappeared

below, among the lighted foliage)

without a soul to put in my mouth.

How many times do I remember

from you, far away

nights of the month of June, how many times

tears came to my eyes, tears

for being more than a man, how much I wanted

morir

or dreamed of selling myself to the devil,

you never listened to me.

But also

life holds us because precisely

it is not how we expected it.

Jaime Gil de Biedma, Nights of the Month of June, Fellow Travelers, 1959

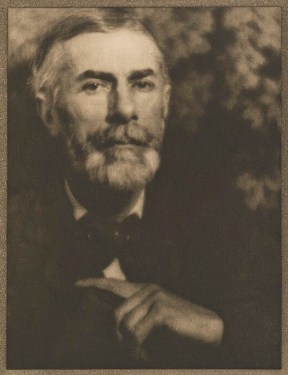

Born in November of 1929 in Nava de la Asunción, Jaime Gil de Biedma y Alba was a Spanish poet. He is considered, among his readers, one of the most proficient Anglophiles in the field of contemporary literature originating from the Iberian Peninsula. Gil de Biedma belonged to the “Generation of ’50”, a group of poets born from the cultivated social realism that arose  in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War. He introduced new techniques into traditional Spanish literature through his use of both dramatic monologue and a diary form of intimate introspection.

in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War. He introduced new techniques into traditional Spanish literature through his use of both dramatic monologue and a diary form of intimate introspection.

Born into a Catalan family with strong conventional values, Jaime Gil de Biedma studied law both in Madrid and Salamanca. As a student in Madrid, he became acquainted with intellectuals such as Gabriel Ferrater and Carlos Barral, both of whom became influential Spanish poets. Gil de Biedma’s lifelong adherence to Anglo-American culture became firmly established by his Oxford studies as a law graduate in 1953 with his reading of works by T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden, and Stephen Spender, who would go on to become United States Poet Laureate in 1965.

Gil de Biedma was also fascinated with the work of Spanish poet Luis Cernuda, a member of the “Generation of ’27” who went into self-exile during the Spanish Civil War. Although separated in age by twenty-seven years, both men had several traits in common: great respect for lyrical English, upbringing in a conventional bourgeois family, openness in regard to their homosexuality, and opposition to the Franco dictatorship. Gil de Biedma exchanged many letters with Cernuda and dedicated his 1959 poem “Nights of the Month of June” to him. In the fall of 1962, one year before Cernuda’s death in Mexico, he published a strong tribute to Cernuda that placed him above all other poets of the 1950s.

a conventional bourgeois family, openness in regard to their homosexuality, and opposition to the Franco dictatorship. Gil de Biedma exchanged many letters with Cernuda and dedicated his 1959 poem “Nights of the Month of June” to him. In the fall of 1962, one year before Cernuda’s death in Mexico, he published a strong tribute to Cernuda that placed him above all other poets of the 1950s.

In regard to his poetry, Jaime Gil de Biedma is a member of Spain’s “Generation of ’50” which included such poets as José Ángel Valente, Francisco Brines Bañó, and Ángel González. The poets in this group, while focused on social issues, were all aware of the literary character of their verse. Partly due to Luis Cernuda’s influence, they introduced to Spain what is now known as poetry of experience, an immediate intellectual experience presented through narration by a fictional-self.

In his work, Gil de Biedma created bridges between English and his birth language of Spanish. He brought his poetry closer to the language spoken on the street by incorporating older Spanish poetic forms such as sestina. Attributed to the twelfth-century troubador Arnaut Daniel, sestina is a fixed verse form containing six stanzas of six lines each, normally followed by a three-line envoi, essentially a postscript in the form of a ballad or dedication. A perfectionist in the composition of his work, Gil de Biedma believed the essential experience in the first reading of a poem was not the understanding of the poem but rather the feeling the verses produce in the reader. The understanding will manifest, sooner or later, when the reader asks why he was so affected.

lines each, normally followed by a three-line envoi, essentially a postscript in the form of a ballad or dedication. A perfectionist in the composition of his work, Gil de Biedma believed the essential experience in the first reading of a poem was not the understanding of the poem but rather the feeling the verses produce in the reader. The understanding will manifest, sooner or later, when the reader asks why he was so affected.

Gil de Biedma published his first work in 1952, “Versos a Carlos Barral”, a series of poems dedicated to his friend Carlos Barral, poet and literary publisher. This was followed in 1953 by “Segun Sentencia del Tiempo (According to the Judgement of Time)”. In his early work, Gil de Biedma strongly criticized the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. The title for his 1952 “Compañeros de Viaje (Travel Companions)” referred to a Trotskyist expression for Communist sympathizers. By the early 1950s, Franco was either suppressing or tightly controlling all political opponents across the spectrum, from communist to liberal democrats and Catalan separatists.

In 1965, Jaime Gil de Biedma published a collection of love poems imbued with eroticism entitled “Un Favor de Venus” which was followed by another socially-themed collection, the 1966 “Moralidades (Moralities)”. In 1969, he published his last collection of poems, “Poemas Póstumos (Posthumous Poems)” in which a disappointed Gil de Biedma confronted himself and the facades he had erected around his personal identity. After this volume, he published poems in various literary journals and wrote his 1974 memoir “Diario de un Artista Seriamente Enfermo (Diary of a Seriously Ill Artist)”. Diary entries from February and April of 1960 reveal that Gil de Biedma was already rereading his 1956 notes; in 1971, he began a lengthy and meticulous reconstruction of the written material.

his personal identity. After this volume, he published poems in various literary journals and wrote his 1974 memoir “Diario de un Artista Seriamente Enfermo (Diary of a Seriously Ill Artist)”. Diary entries from February and April of 1960 reveal that Gil de Biedma was already rereading his 1956 notes; in 1971, he began a lengthy and meticulous reconstruction of the written material.

As a homosexual during a strongly conservative period in Spain, Gil de Biedma was essentially forced to lead a double life. As part of a conservative family and, since 1955, holding an important position in the family’s Compañia General de Tabacos de Filipinas, he was a discreet and respectable executive. In the company of close friends, Gil de Biedma was openly gay with a quick wit and sharp tongue. At different times, he had suffered discrimination and blackmail. Gil de Biedma’s poetry was a reflection of this duality as, while he explored themes of love, romance and sex, he never disclosed the gender of the loved one.

Even at the end of his life, Jaime Gil de Biedma was adamant about keeping his poetry neutral. After learning that a journalist wanted to analyze his work from a gay literary point of view, he was distressed and went through great trouble to ensure that the journalist would not take that approach. Ten years before his death, Gil de Biedma stopped writing poetry. He had decided that the persona of the poet James Gil de Biedma had nothing left to say and, subsequently, abandoned that role in literary society. Three years after being diagnosed in 1987, Jaime Gil de Biedma died in Barcelona on the eighth of January in 1990 from complications due to AIDS.

Notes: For the thirtieth anniversary of Jaime Gil de Biedma’s death, Javier Gil Martin, a collaborator of the Adiós Cultural magazine, wrote an article on Gil de Biedma’s “Posthumous Poems”. This article can be found at the Adiós Cultural site located at: https://www-revistaadios-es.translate.goog/articulo/165/JAIME-GIL-DE-BIEDMA-/-POEMAS-POSTUMOS.html?_x_tr_sl=es&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

Director Sigfrid Monleón’s 2009 biographical drama “El Cónsul de Sodoma (The Consul of Sodom) is a journey through the work and life of Catalan poet Jaime Gil de Biedma. It premiered at the San Sebastián International Film Festival in 2010. The film received five nominations at the Goya Awards, including Best Lead Actor (Jordi Mollá) and a Gaudi Awards nomination for Best Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role (Jordi Mollá).